[Translate to English:] text 1

Pilgrim's Tattoos

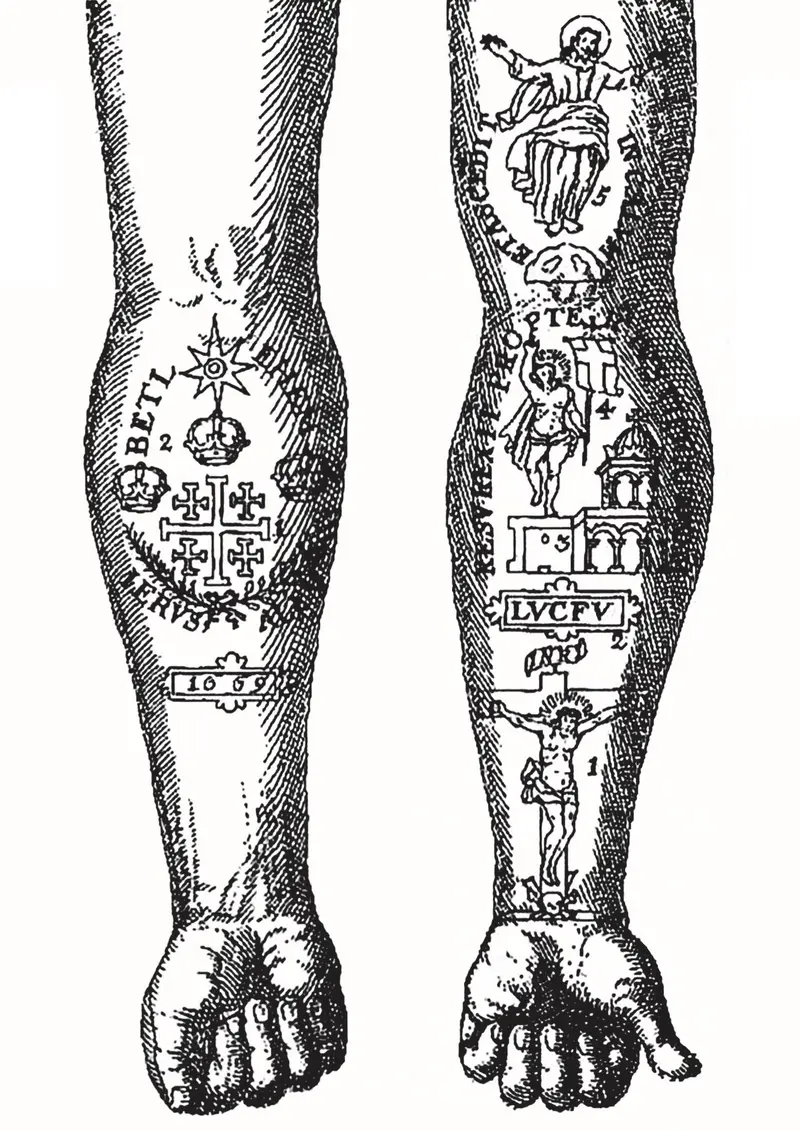

For pilgrims to the Holy Land, tattoos served as proof and as a souvenir of the visit to the Holy Sepulcher and other Christian sites in Jerusalem. It is stated in the Old Testament: "Ye shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor print any marks upon you. I am the Lord" (Lev 19:28). And yet, pilgrim tattoos were popular. Members of Christian minorities in Armenia, Syria or Ethiopia mainly used this custom. To this day, families like the Coptic Christian family Razzouk from Jerusalem maintained this ancient tradition of tattooing in their own tattoo studio. For hundreds of years, Christian pilgrims have been decorated with the symbols of their faith: holy symbols such as the Jerusalem cross and sacred images such as the resurrection of Christ or St. George, the dragon slayer.