[Translate to English:] text 2

Through graphical illustrations of the expedition reports, such as those by von Krusenstern’s travel companion, the naturalist and physician Tilesius von Tilenau (1769-1857), Europeans were given a visual idea of tattoos. In light of the aesthetic ideal of classical antiquity, the artist presented tattooed people as unspoiled wild people in paradisiacal landscapes. This image of the "noble savage" influenced the romantic transfiguring image of the Pacific from the 17th up to 19th century and fueled the fantasies and desires of Europeans. What followed was the (often forced) presentation of numerous residents from the Pacific as an exotic spectacle to audiences in so-called “Volkerschauen” and in salons throughout Europe. In turn, tattoos aroused particular attention and inspired tattoo art in Europe through their designs.

In ethnological museums, the numerous material objects of the inhabitants of the Pacific were shown in a similar romanticized context. For example, the two oil paintings by Bruno Geisler (1857-1945) and Hans Jäger (1887-1955), which can be seen in the exhibition and were on display at the Museum of Ethnology Dresden from 1911 until the Second World War, tend to illustrate the "living conditions" as ideals of the "South Pacific". The paintings are based on the photographs also shown here, whose scenes depicted appear far soberer.

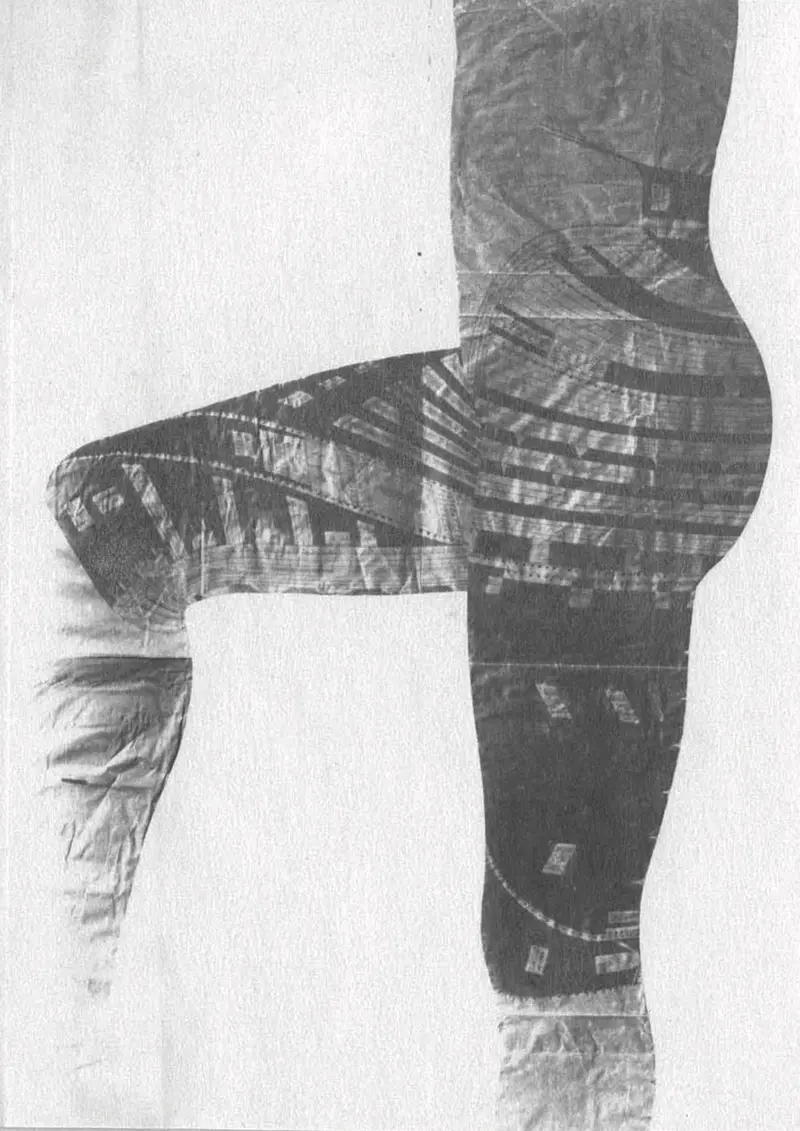

At the beginning of the 20th century the sojourn of the Leipzig surveyor Julius Henninger, who served the colonial government in the colony of "German Samoa," resulted in a life-sized ink drawing of a pe'a (the tattoo of the Samoan man) in 1916, which is exhibited here. The preoccupation with tattooing went so far, that German colonial officials, even the governor Erich Schultz-Ewerth (1912-1914), allowed themselves to be tattooed to achieve colonial-strategic goals by appropriating Samoan practices.